Saint Andrew in Art

Saint Andrew in Art: A Journey Through Time

From the luminous austerity of medieval stained glass to the glowing sentimentality of Victorian revivalism, the image of St Andrew the Apostle has undergone a remarkable evolution. His story — the fisherman called by Christ, the missionary martyred upon a diagonal cross — has been retold in every age through the visual language of its faith. Each artwork preserves not only the saint’s likeness but also the theological and artistic temperament of its time.

The Medieval Saint — Faith and Geometry

The early 14th-century stained glass at Saint-Ouen, Rouen (1325–1339) presents St Andrew within the disciplined order of Gothic design. Here he is a hieratic figure: solemn, frontal, and defined by linear rhythm rather than individual expression. The X-shaped cross, his instrument of martyrdom, stands as both emblem and geometry — a sign of divine symmetry. The figure’s restraint mirrors the medieval church’s ideal of the saint as intercessor, remote yet radiant, existing in the abstract harmony of light and colour.

This was a time when the image of Andrew served not as portrait but as symbol — a spiritual constant in the architecture of salvation.

Renaissance Narrative — The Martyrdom as Human Drama

By the early 16th century, the saint’s story had taken on new emotional and physical life. In the 1520 panel from Évreux Cathedral, the Crucifixion of St Andrew unfolds within a world of bodily movement and architectural realism. The saint’s suffering is tangible, his limbs twisted against the cross, his humanity newly apparent.

This is the Renaissance transformation: salvation becomes personal, faith incarnate. The artists of Normandy, absorbing Italian influences, began to frame Andrew’s sacrifice as both historical and human — a man who endures pain with grace rather than a stylised icon of endurance.

The Domestic Devotion of the Tudor World

In contrast to such grand ecclesiastical works, the small painted-glass panel at St Mary’s, Fawsley — likely from Sulgrave Manor, c. 1550–1600 — represents the saint in miniature. Here, Andrew stands simply with his cross, painted in ochres and soft enamel against plain glass.

The modesty of the design reflects a new age of private faith. Following the English Reformation, religious imagery retreated from cathedral splendour into the intimate world of manor chapels and domestic piety. In these small fragments of glass, the saint remains present — not as the focus of public devotion, but as a quiet companion to personal prayer.

Baroque Passion — The Hero of Martyrdom

By 1714, the image of St Andrew had become a study in movement and emotion. The low-relief sculpture in San Gaetano, Florence, shows the saint at the moment of his crucifixion, his body twisted and muscular, surrounded by Roman executioners. This Baroque interpretation, all dynamism and drama, transforms the martyr into a hero of divine will.

Gone is the static holiness of the Middle Ages; here, the artist seeks to make the invisible visible, the ecstasy of faith rendered through the body’s agony. The saint’s raised eyes and open arms embody the theology of sacrifice as transcendence.

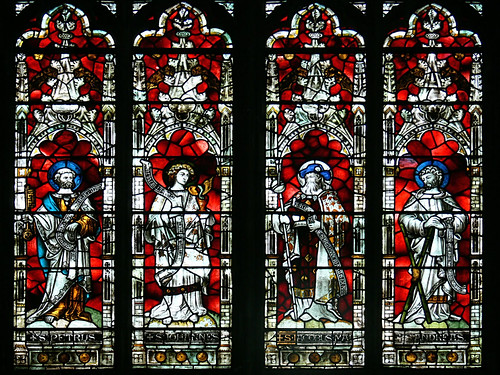

Victorian Renewal — Apostolic Companionship and Faith in Colour

Nineteenth-century Britain rediscovered Andrew within the context of revival and reform. The Clayton and Bell panels at Gloucester Cathedral show him among his fellow apostles — dignified, contemplative, and restored to the Gothic splendour of coloured glass. His cross is no longer a sign of torment but an emblem of steadfastness.

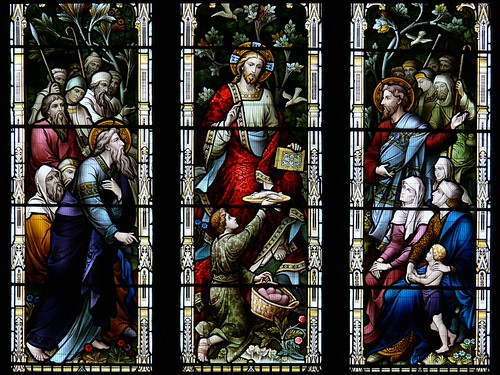

In the Tewkesbury Abbey window by John Hardman & Co. (1888), Andrew reappears in narrative form, gesturing to the boy who brings the loaves and fishes to Christ. Here, his faith is active, compassionate, and instructive. The Victorian Andrew is not a martyr in pain but a teacher and participant — a moral guide for the modern believer.

Conclusion — Light of Continuity

Across seven centuries, St Andrew’s image has shifted from symbol to story, from suffering to service. In the Middle Ages, he was a still point in divine geometry; in the Renaissance, a human witness to martyrdom; in the Reformation, a companion of quiet faith; and in the Victorian revival, a model of devotion reborn in colour and grace.

Yet through every transformation, one truth remains constant — the saint endures in light. Whether in fractured medieval glass, carved marble, or painted enamel, his presence reminds us that faith, like stained glass, is made strong by its fractures and beautiful by the light that passes through.